THE COMPASS

Olivia’s Journey

“Olivia’s Journey” features excerpts from Wendy Beaudoin’s blog, which details her experiences with her daughter Olivia as she undergoes surgery. You can read more and follow along at facebook.com/neurosurgerykids

December 31, 2013

Tags: anger, other children, what if?

As soon as I opened my eyes this morning, I was in a bad mood. I felt irritable and annoyed and hadn’t even gotten out of bed. With a million little things to do to get ready for a prolonged stay in the hospital, I decided I would spend quality time with my other two kids, Kenzie (nine years old) and Jake (six years old) and get some errands done.

Right now, Olivia can’t stand for more than about five minutes without getting a blinding headache. By 10 minutes, her brain sinks into the top of her spinal cord and makes her neck hurt and her hands so weak she can’t hold her juice box. It would be impossible to take her shopping, so once again I call on my mom to come over and stay with her while we head out.

We’re at the mall when we bump into an old friend. The conversations ends with her saying, “Well good luck with everything. I hope she comes through it OK.”

I walk away and hear Kenzie quietly say, “What does she mean ‘I hope she comes through it OK’? It’s not like she’s going to die…” I see her eyes well up with tears as she looks down and it stops me in my tracks.

I give her a hug and say, “She just means she hopes she isn’t in too much pain and that we’re home quickly.”

She swallows her tears and says, “Well why don’t people just say ‘good luck’ then?”

When I get home, I get a text from my husband Brett who works out of town during the week. He has been working a lot so he can take off as much time as he needs in January. His plan is to work until Sunday so he can come to her pre-admission visit Monday and then be off for the next few weeks as necessary. He asks me a simple question about what we’re doing on Sunday, and I fire back a text that is clearly designed to start a fight. I just want to be mad today and I can’t seem to find anyone to be mad at.

I am mad that I can’t work at the job that I love. I am mad that my neighbour runs over to see how Liv is doing and says, “I don’t know how you do it,” as if I actually have a choice in the matter. I’m mad she was born 16 weeks premature, and I am tired of being the mom of a sick child. He sends me a text back, clearly confused as to why I’m freaking out over something simple. We text back and forth and I send my last text which basically says, “Do whatever you want. You’re going to anyway.” There is a pause in the texting and a couple minutes later my phone rings. I stare at it, wanting to press the decline button, but I answer it anyway.

“You OK?” he asks. My eyes fill up with tears and I quickly head into our office and close the doors. I was going to say something like, “I need to get groceries and you could help clean the house on Sunday,” but – surprising even me – I quietly say, “What if she dies on Tuesday? What if you spend the last two days of her life working and regret it?” I know the odds of her not surviving the operation on Tuesday are slim. But every time she goes to the operating room, I think about it the entire week before. I think, “What if this is the last Christmas we have together, what if this is the last movie we watch together and what if this is the last Monday we spend together?” They are fleeting questions that I don’t allow myself to answer.

Brett responds, “I have been thinking the same thing all week. I’ll be home Thursday night.” I realize that he was just waiting for me to ask him to come home. That even more than I need him home, he needs to be here. I feel overcome by calm.

I saw a psychologist today. Yup, that’s right. Actually that’s not exactly true. I wrote it, erased it, wrote it, erased it and then finally wrote it again.

It’s not that I think psychological help isn’t insightful and smart. I recommend it on a daily basis to the caregivers of the patients I take care of and truly mean it. Your child becoming sick, whether it is a life-long illness or a sudden event, is debilitating; it’s like you can’t breathe and have no idea how to come up for air. I am a fan of psychology, plus or minus medication, to help anyone cope.

Olivia has seen a psychologist for four years. It started out working on a needle phobia, and continued on to the concept of what being normal is, and how to cope with the lack of normalcy in her life. She walks a little bit taller every time she leaves her psychologist’s office. Even I look forward to those appointments. But in 10 and a half years and over 29 operations, I’ve never sought help. So why now? The truth is, I wouldn’t have seen anyone if it weren’t for my best friend. I’m lucky to have a best friend who has been there through every single step of this journey. It’s surprising how many friends you lose when you have a sick child. Not because they are evil or even uncaring but because the novelty wears off, and when you constantly have to cancel plans or have a child who isn’t quite as quick or mobile as others, people naturally move on. This happens with friends even if you don’t have a sick child, I suppose; I just think it hurts more when you do. But this isn’t the case with my best friend.

I was thinking about Olivia and it hit me out of the blue, like a ton of bricks: “This is never going to go away.”

Her push for me to see someone stems from the fact that I can’t sleep. Over the last few years, I have eluded sleep for extended periods of time. I can remember when my trouble sleeping started. It was a couple years ago. There really wasn’t anything remarkable about the day, but still I remember it so clearly. I was driving to the grocery store in the evening to grab a few things. I was thinking about Olivia and it hit me out of the blue, like a ton of bricks: “This is never going to go away.” I thought that if I read enough, worked hard enough, or was just good enough, that at some point I’d be able to stop worrying about her. The realization that there was never going to be an end to her illness was staggering. I pulled over into a parking lot and just cried. I didn’t sleep more than two or three hours a night for the next several months.

The next time I couldn’t sleep for an extended period of time was last year when Olivia suddenly became quite sick. She had been at school, three months after a spinal shunt revision, when I got a call from my nanny who said Olivia was crying hysterically and the back of her t-shirt was wet. I called my mom to bring her up to the hospital where I discovered her back incision had opened up. Over the next couple days they tried to sew it back together but the incision kept falling apart. Finally they admitted her and took the spinal shunt (a tube that runs from her spine to her stomach to drain her spinal fluid) out in an effort to give her back a rest and see if she even needed it any more. The first day was fine. We were overjoyed that we might be able to go down to just a VP shunt (a tube that runs under her skin from the middle of her brain to her stomach). The next night she woke me up at 1 a.m. and I could hear her throwing up. When I came out of the room she was holding her head crying.

The next few days were a blur. By mid-morning, her neurosurgeon and pediatrician were there and everyone looked incredibly worried. Over the course of the day she developed double vision, became unconscious and was intubated. The next two days were spent in the operating room taking her skull apart and reconstructing it to give her brain more room to swell. I slept in a chair with my head on the foot of her bed. She was in the intensive care for 10 days and then moved to the regular unit. The next day she started to throw up again, and at 4 p.m. on Christmas Eve doctors put a new spinal shunt in. When she was able to walk again, her right leg didn’t work well and she was incredibly weak. I didn’t sleep from December to March. I barely remember any of those months. It’s like having PTSD, but no one thinks of that for trauma related to our sick kids. I remember not wanting to have visitors, not wanting to go anywhere, and crying a lot.

Which brings me to the past month. This has been the longest time we’ve ever waited for an operation. Normally for shunted kids, they get sick and get their shunt is revised in a matter of hours or a few days. We have been waiting for a system to come from two different countries and for her neurosurgeon and pediatrician to return from holidays. The waiting is awful. Every day I wonder if we are making the right decision. Every day I go over what could possibly go wrong and what the options are if things do. Every day I worry. Every night I don’t sleep. This time my best friend pushed me to seek counselling, and this time I was ready to accept the help.

There are six days until her operation. I’m hoping for some sleep before then.

Today was a day of errands. With just five days until Olivia’s operation, it’s like planning for the worst vacation ever. Doing laundry, cleaning the house and preparing meals and necessities for the hospital. Over the years of doing this, I’ve learned some helpful tricks – things like stocking up on Superstore fleece pajamas at Christmas time, as they are MRI compatible and the arms are wide enough to fit an IV through them easily; buying the colouring books at Walmart that have adhesive tops so they stick to the walls of her hospital room without tape; buying a brand new pack of the Crayola thin markers, because they are light and easy to color with when her hands aren’t working right; and making sure I have warm pajamas, as the air conditioning vents are conveniently located right over the parent cots.

I’ve learned to pack our own pillows, because sleeping on a rubberized pillows sucks, and I make sure we have a blanket that will cover her entire bed to try to hide the all too obvious “medicalness” of the hospital. I also spent part of the day organizing her schoolwork and making sure her school laptop is up-to-date. Trying to manage school when you are constantly in and out of the hospital can be a challenge, overwhelming at times.

I remember the day we were told there was a problem with Olivia’s brain. She was just eight days old and a resident came in and told us she had a massive bleed in her brain, and that she would probably never walk, feed herself or see. I remember him patting me on the knee and asking if I had any questions. I barely squeaked out a “no,” so stunned I could hardly move. A few hours and a few thousand tears later, the neurosurgeon walked in the door. He checked her out and quickly reassured us that the location of the bleed couldn’t have been better. The bleed was largely in her ventricles (the fluid filled lakes in the middle of your brain) and not in the brain tissue. He said, “She will do great, Wendy. She will need some surgery and may have some learning disabilities, but otherwise will do quite well.” Brett and I burst into tears of relief and I said out loud, “If all she has is learning disabilities, I will never complain.” I didn’t know how painful learning disabilities could be.

In the first grade, we started to notice how hard it was for her to understand math. It was incredibly frustrating for her to do homework assignments. I would sit with her to work on the simplest of concepts, like counting by fives, and I realized that she couldn’t grasp it. When she finally did grasp the concept we would go on to something else. If we came back to that concept five minutes later, it was like she had never heard it before. She had problems with short-term memory. I remember wrestling with what to do. I felt incredibly guilty for feeling so disappointed.

Every day I work with families that lose their child, families that would literally give everything to be able to worry about a learning disability instead of trying to survive their first, fifth or even 10th start of the school year without their pumpkin. Knowing these families has changed me as a person and as a parent. Each one of these kiddos, whether I knew them for eight days or eight years has made me a more grateful person, a more diligent clinician and a more patient mother. I knew I should be able to accept her learning disability and just be grateful to have her, but I couldn’t.

I think any kid who has brain surgery should get a “get out of jail free” card for academics. They should be brilliant, school should come easy to them and they should have every door in the world open for them to choose the career of their choice. But it doesn’t work that way. In fact in most cases, it’s the exact opposite. These kids fight so hard just to survive and then they have to struggle every day in school. It’s unfair. Even more than worrying about expecting too much from Olivia, I worried that I wouldn’t expect enough.

I remember the day we were told there was a problem with Olivia’s brain. She was just eight days old and a resident came in and told us she has a massive bleed in her brain, and that she would probably never walk, feed herself or see.

I remember sitting at the table one evening doing homework with Olivia and Kenzie, as Kenzie whipped through her assigned homework and I gave her a few extra math sheets to work on. When Olivia finished her math, 45 minutes after Kenzie was done, she asked me if she needed to do any extra math sheets. I said, “No, that’s OK, you’ve been working at it long enough.” Not looking up at me she said, “Mom, why do you expect less out of me than Kenzie?” I had no response, because the truth was, at that time, I did.

I come from a very academic family. From the time we were little my parents would ask us what we were going to take when we got to university, not if we got there. I always assumed I would have children who would do the same thing. That’s not to say I was always a good student; I barely scraped by in high school until one day my dad sat me down and said, “You know Wendy, not everyone is meant to go to post-secondary education. We just want you to have a career and work hard at it to be the best you can be.” In my teenage rebellion I thought, “Screw you, I am going to study hard and I will show you when I get in.”

As Olivia moved forward in school, it was clear she would need some help. I had no idea how to navigate the school system. We had private neuropsych testing done to understand how she learns, but I didn’t know how to translate that into the real-world classroom environment. Thank goodness for Brett’s uncle, the principal of a school. Otherwise, I would have completely lost my mind by now. He would tell me to go to the school and ask for various things. I would put on my big-girl pants and march down to the school to politely ask for what he had suggested only to get a “Sorry, we can’t do that Wendy,” and I would leave feeling confused and frustrated.

I would call him and say the school can’t do whatever it is he wanted. He would ask me to repeat the conversation. He would then direct me to go back and say what seemed to me like the exact same thing with one or two words changed and I would magically get a “of course we can do that.” That was when I realized that this was an area of her life that we would never be able to fix on our own, we would always need help. Even with help navigating the school system, I completely underestimated how heartbreaking it is to watch your child struggle to learn. It is like when your child is the only kid not invited to the popular kid’s birthday party, only every day for the rest of their school life. People often say, “Well, she just may never go to university,”

I know I am supposed to think, “Well that’s ok, she’s alive and that’s good enough for me,” but I don’t. I feel sad and mad and annoyed, every time.

In the last couple years, I’ve had to understand a whole new area of technology related to learning. I have learned about apps that shortened the length of an article, dictation programs, pens that you can record on, programs that can anticipate what she wants to write, and I have learned how to be a squeaky wheel, but not too squeaky, at school so her needs are met. I pushed her to work on a laptop all the time so she can have her school work with her whether in the hospital, on the couch or in the class. I learned to let some old-school ideas go – like she needs to memorize the times tables – and accept that she will always need a calculator to figure out fives times five. I have learned how to stop trying to “fix her” academically, and instead focus on finding new and innovative ways to maximize her strengths and minimize her weaknesses. In truth, I had to get over myself and focus on her. I’m not quite there yet. I still wake up every day hoping school will just click for her, and every day won’t be such a challenge. Selfishly I wish the ache in my heart that comes with watching her struggle would subside, but it hasn’t, yet.

There are five days until we head to the hospital. It is hard to decide if I want the time to speed up to get the surgery over with or slow down so I can have more time with her.

I lay in bed this morning with a numb arm. When I woke up, Olivia had assumed her usual position when she isn’t feeling well and was asleep with her head in crook of my arm, managing to cut off the blood supply to my fingers. But I didn’t move. Like many parents when they catch a moment of their sleeping child’s peacefulness I stare at her and gently kiss her head feeling overwhelmed by how much I love her. When I kiss her head I can feel where she is still missing the bone in her skull from last year’s operations, and notice the railroad tracks of scars that crisscross her head, but they truly don’t bother me. All of these little things, and big things, make her who she is and make us who we are as a family. I couldn’t love her more for that.

There is something about medical children that is different from others, not better, certainly not worse, but different. It took me years to see a pattern in all of the children that I take care of who have had significant medical events in their lives, but I see it clear as day now. I can pick out a child who has had multiple surgeries even before I even know their history, something that at times makes me look psychic to my loved ones. They are old souls in little bodies. They feel more deeply, love more strongly and unfortunately fall harder than the average child. That’s not to say that every child who has had a hangnail removed is like this, but if you have a medical child in your life, you know what I am talking about.

Finally Olivia begins to manifest the stress of the situation and I see her get progressively grumpier as the day of the operation nears, with Jake getting the brunt of her anger. I give her a few minutes and then knock on her door. Through tears she says, “I just want to be alone.” More than anything I want to open the door and make everything OK, but I give her a few minutes to cry it out.

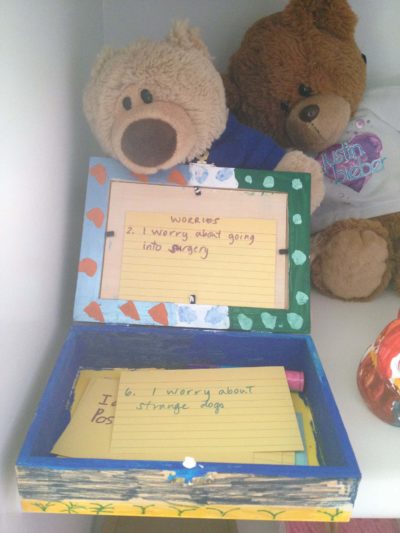

When I come back upstairs, I listen at the door and can’t hear her crying. I assume she has fallen asleep but when I open the door she is laying on her bed writing on some index cards. I lay down beside her on the bed and listen to how annoying Jake is and how much better our family would be if we just had all girls, “Except for Daddy, but he doesn’t count.” I ask her what she is working on and she looks down a bit embarrassed and says, “I am writing down some things I am worried about and putting them in this box.”

I’m actually not sure what to say. I want to read all the cards to see what is on her mind but don’t want to have her shut down if I push. “Can I read what you wrote?” I ask.

“Sure,” she says, but reaches in the box, riffles around and takes two cards out and shoves then under her pillow. Of course those are the two I really want to read, but I pretend I didn’t see her do it.

“So you are writing down what you are worried about and going to bring the box to the hospital with you? I think that is brilliant Liv. Very grown up.”

She is still looking down colouring on one and says, “No. I am going to leave the worries here on my shelf so I don’t have to worry about them when I am in there.”

I am speechless. I have seen this box on her shelf for years. In fact we just cleaned her entire room two days ago and I wanted to throw it out, but she quickly grabbed it and said she wanted to leave it on her shelf. I assumed it had some kid treasures in it like rocks or stickers or nail polish, but now I understand why. My hands shake a bit as I look pick up the cards, not sure if I am ready to read what she has written. The first card I pick up says, “6. I worry about strange dogs.” I am relieved to see a normal kid worry on the card. She reaches over and turns the card over in my hand. “On the back I write what I can do so I am not so scared,” she says with some pride. This one says, “I just ask the owner if the dog is friendly.” It seems logical to me, and I smile a little. The next card reads “2. I worry about going into surgery.” I turn the card over and read, “I can hold my mom’s hand when they put the mask on my face. I have done this 29 times and I am OK.” That one hurts a bit more. I want to ask her some comforting question about what specifically she is worried about, but I can’t put the words together so I just keep reading.

“3. I worry that my IV needle will get stuck,” it reads. “I ask my mom if that’s possible. She won’t lie to me.” I am trying desperately not to let the stinging in my eyes spill over my cheeks and risk breaking the magic of this moment. “4. I worry that I won’t recognize people when I wake up from the operation,” and “I just ask my mom who people are.” The first tear slides down my face. Then comes the card I am dreading, the one that I know must be in here.

“1. I worry that I won’t wake up and no one will remember me.” I fall to pieces, the tears streaming down my face, and I try not to make any noise. She looks up at me from her colouring, but doesn’t say a word and looks back down. Through blurred eyes I read the next one, “5. I worry that my eyes will get swollen again and that they will never open back up.” Last year after one of her operations her eyes swelled shut for a day or two and it scared her to death as she thought she was blind. Since then she won’t sleep with her lights off. It doesn’t surprise me that this is a worry, but doesn’t hurt any less either. And the last card reads “7. I worry about strangers,” with “My mom tells me who it is. I can ask ‘What’s your name.’ At first I am shy then I get to know them.”

There are two other cards in the bottom of the box, one written in an adult’s handwriting and one written in hers. I realize that this idea must have come from

her psychologist, whom she trusts so completely. The card written in adult writing says, “Being brave means doing something even though you are scared,” and the card written by her says, “Olivia’s coping strategies: When I get scared I can: one – do some deep belly breathing, two – think of fun memories like my old house, three – I can bring a book to read or four – I can watch TV.” When I regain my composure I can’t help but wonder what could possibly be on the other two cards that could be more heart wrenching that these. The truth is, I don’t want to read them anymore. Then I put all of the cards back in her box and ask her if she needs anything. She says she doesn’t but I grab her some cookies and milk and put it on her bedside anyway. When I am leaving the room I kiss her on the head and tell her I am proud of her. She gives me a shy smile and says, “I know, Mom.” I am constantly amazed at how much I learn from her and I wonder if I’d be able to leave my worries on the shelf like that. What a relief that would be.

I ask her if she would mind if I share the cards with some other people. She of course asks me who and why, and I explain the blog. She asks me why adults would be interested in her cards and I explain that sometimes hearing someone else’s story helps people to cope with their own. She gives me a simple “sure,” but I can tell she is proud that any adult could learn anything from her. She asks me if she has to include the two cards form under her pillow and I say, “Only if you want to.” She thinks for a minute and says “No, I think I’ll just keep those ones,” and secretly I’m relieved. I love that she is assertive enough to know her own boundaries.

Three more days until her operation.

It’s funny to me how walking into the hospital as the parent of a patient is so different from walking in there as an employee. The hospital itself actually smells different, looks different and feels different. Shortcuts I would normally take suddenly feel off limits. Even using my key to go into my own office somehow feels wrong.

We had to be at the pre-admission clinic for 1 p.m. today. All morning I checked off items on my “Hospital To Do List.” Slippers. Check. Markers. Check. iPad charger. Check. As I quickly complete the list I hear my phone buzz. Incoming text. I grab my phone half looking at it while I’m reading the last few items on the list. There is a text from her neurosurgeon. Surgery has been postponed until Wednesday. My heart sinks. Not because she is super sick today or anything, but because there is something about the psychology of getting prepared for the hospital that is not conducive to adding in another day. I have things timed down to the minute so we have enough time to get everything done, but not too much time to have to think about what is coming.

Brett and I have been very lucky to have a surgeon who is the perfect fit for us. He is very honest and straightforward with little to no sugar coating.

I stare at my phone for a minute trying to decide if I want to call and see if there is a way that the surgery can still be done tomorrow, but quickly snap out of it. I know the million reasons that surgeries can be postponed and none of them are “just because.” We have bumped other children when Olivia has been critically ill, causing other families the same angst I now feel. We have been bumped before. It is unfortunately just another aspect of the whole process that is out of our control. Brett has run out to do some errands so I text him the news. I text a dozen other people who had plans that either involved coming to the hospital or taking care of my other two children. Then I turn to the couch to tell Olivia. She immediately bursts into tears, frustrated that she has to wait another day. I point out all the advantages of waiting, which actually help me feel less disappointed. “We can have Samantha (her best friend) and their family over for dinner and you and I can finish the level on Luigi’s Haunted Castle,” I say as she wipes the tears from her face. “Promise?” she asks. “Of course,” I say texting Samantha’s mom right away to prove to her I mean it.

We still have to head to the pre-admission clinic for 1 p.m. This is always the most important appointment for Olivia because she gets a chance to speak to the doctor who will put her to sleep. She desperately needs the reassurance that they will start her IV when she is asleep and this is her chance to make sure it will happen the same way it has 29 times before. When we get there, her neurosurgeon and Stacey are waiting for us. She hugs them both and we head in to the clinic to chat. It’s funny how people connect with different doctors. You can have the same personality trait in a surgeon that will be perfect for one family and not so great for another. One is not necessarily better than the other, just a better fit. Brett and I have been very lucky to have a surgeon who is the perfect fit for us. He is very honest and straightforward with little to no sugar coating. For me this is essential, but at times it can sting a bit. He sits down to talk to Brett. He and I have hashed out what needs to be done a million times during clinic appointments and phone calls, and this is his time to talk directly to Brett. I listen intently as he goes over the history of where we have been, what the current problems are, and where we need to go on Wednesday. I know it all but I listen like it’s brand new information.

Then come the two things I know he is going to say that I dread: “In case this doesn’t work….” and “If we need to do something else…” I know logically there are no guarantees, especially in neurosurgery. I know this isn’t a sure thing, otherwise we wouldn’t be on operation number 30, but every time it makes me flinch. Don’t get me wrong, I would much rather have the sting of this conversation before the operation, than the gut wrenching disappointment of something happening that we didn’t know was a possibility. When he is done he leaves, and the anesthesiologist comes in to see if we have any questions. Usually I make Olivia ask the questions she has, as I think she needs to learn to advocate for herself being that she will always require surgical care and at some point she will be an adult and responsible for her own medical journey. It scares me to death even thinking about that, but that doesn’t make it any less of a reality.

She asks the doctor, “Can you gas me tomorrow?” I hate it when she says that. It sounds so morbid. The anesthesiologist knows exactly that she means – can she be asleep before they start her IV? The doctor says she doesn’t think it will be a problem. There are no promises, but it should be OK. “Well done,” I think. Another thing I have learned in dealing with sick children is never to promise anything you don’t know you can deliver. If things don’t go as planned, they will never trust you again. The anesthesiologist we are seeing today will not necessarily be the doctor putting her to sleep on Wednesday, so she doesn’t give her an absolute yes, but the answer is good enough to calm Olivia enough that she flips open her Nintendo DS and starts to play it again.

When we are done and driving home, Olivia pipes up from that back seat, “I can’t wait to get this over with and go skiing in Jasper next month.” Without thinking I say, “Oh Liv, you won’t be ready to ski next month.” Damn it. Rookie mistake. I should have just let it slide today. There will be plenty of time to discuss it in the coming weeks. She immediately burst into tears. “I hate having surgery! It’s so unfair! Everyone has a better life than me! Everyone gets to do fun things and I just lay on the couch doing nothing! I hate my life!” she shouts almost incomprehensibly through her sobs. I immediately retreat and say, “Let’s just see how it goes, that’s a long time away,” but it’s too late. She sinks down in the back seat with her head on the arm rest, as her crying has increased her headache tenfold. I’m so tired.

We get home and continue with our plans to order Chinese food, Olivia’s requested meal. Brett hates the “favourite meal before an operation” ritual. He thinks it’s like a prisoner’s last meal before an execution. But it’s tradition, and she requests the meal even before we ask her because she finds so much comfort in the routine. Immediately after dinner she asks to go to bed. It’s been a long day, long month, long 10 years.

Have a good sleep kiddo. I love you.

The operation is tomorrow morning at 7:20 a.m. We have to be at the hospital for 6 a.m. and we have to get Olivia up at 5 a.m. to wash her hair with the pre-op shampoo. I’m dreading it as I know she will cry from the time she opens her eyes until she goes to the operating room, out of fear. She will plead for me not to take her, then get mad and then cling to both of us as we walk down the long hall to the operating room.

As soon as she opens her eyes, she says, “I don’t want to go Mommy.” It’s always “Mommy” when she is scared.

“I know kiddo,” I say, “but just think – in a few hours it will all be done.”

“Do you think we can do my Lego tonight when I wake up?” She asks.

“Of course honey,” I say, and she smiles and reaches across to give me a big hug. I go downstairs to finish packing the other two lunches. I hear my mom open the front door and tears spill over my cheeks. There is nothing like having a sick child to make you feel like a child again.

Two hours down, three to go. Seems like time is crawling by. I’m so tired.

As I lay here on the cot, the step-down ICU is quiet, but my thoughts are not. What a day. I forget each time how overwhelming this whole process is. The day went by in the blink of an eye and even now, I can only remember snapshots of it. While it’s an exhausting process, it is one that amazes me every time. At times I hear people complain about our health care system, and while I agree that there is certainly room for improvement, I marvel at the number of people it takes to make sure my child receives exceptional care.

The nurses in the pre-admission clinic check on us several times to see if we need a blanket, a pillow, the lights on, the lights dimmed or even a hug. Exceptional. Olivia’s operation is delayed due to a trauma that required many people to work through the entire night. Instead of then requiring that same staff to work all day or cancelling Olivia’s operation, the doctors and nurses juggle complicated scheduling to make sure that my daughter is cared for by well rested and competent staff. Exceptional.

We walk in to the operating room and a nurse, immediately gets her a warm flannel blanket, while another nurse makes an exaggerated comment about how beautiful her hair is and smiles.

While we are waiting, her neurosurgeon wanders by to see how we are holding up. He stops to tell us a funny story about something that happened on his Christmas holidays which makes both Brett and I laugh out loud, something we couldn’t have needed more at that exact time. Exceptional. When it is finally our time to go to the operating room, a porter comes to walk us down. He addresses Olivia by her name, asks her if she needs anything, and makes a point to tell her a funny joke as she is clearly nervous. I grab my phone to take it with me and glance at it realizing I have more than one hundred messages. Messages of love, kind words, caring and above all else, hope.

When we get to the OR, the anesthesiologist, the one who was not supposed to be doing Olivia’s case but was flexible enough to come in to her theater and help out, comes in to talk to her. He asks our opinion on what works best for her for pain, asks which hand she writes with so he can make sure he puts her IV in the other hand because he knows she loves to colour and is more than happy to give her an immunization while she is asleep so she can have one less poke while awake. We walk in to the OR and a nurse immediately gets her a warm flannel blanket, while another nurse makes an exaggerated comment about how beautiful her hair is and smiles. When she is asleep, they let me kiss her cheek and one of the nurses walks me out of the operating room, then gives me a big hug and promises me they will take good care of my daughter. Exceptional.

We grab her stuff and walk out to the cafeteria where my sister Julie and brother in law TM are sitting. They drove in from Calgary, like every operation before, to be there for Brett and I when we need them the most. Exceptional – especially in light of the fact TM just had surgery on a broken leg a few days ago. In the meantime, Aaron has picked Kenzie up to drive her to school and Kurt and Marnie have offered to treat Jake to an amazing day to keep his mind off the fact that both Brett and I are not around. Exceptional. By the time we get up to her floor and check in at the desk on the Pediatric Surgical Unit, my mom has texted me to see if we need anything. Normally she would be in Phoenix by now, but she stayed back to help Brett and me with the kids.

We sit and wait for the operation to be over. Old friends Stacey and Carolyn show up, as always, to bring food and make us laugh. Exceptional. New faces Martin and Wendy bring hugs, laughs, food and above all friendship to help the time pass. Exceptional. All the while, dozens of people stop by and hundreds of texts roll in to keep our spirits high. They’re a welcome distraction from all of the worry. When Olivia gets back, tired, disoriented and in pain, the nurses react quickly and with amazing competence to get her moved in to bed, pain medications administered and tuck her in with warm blankets. Her neurosurgeon and both pediatricians have already stopped in to assess her and make sure her post-op course is going as planned. Exceptional and critical.

Natalka pops in with gifts of warm blankets and tears of love like she always does. Aaron and Carolyn come back up to the hospital to bring the all-important pizza and Liv’s two best friends Sammy and Lila to make her happy. Melissa shows up with gifts and snacks from so many good friends and well-wishers that I am stunned and Olivia is thrilled. Ideas flow about new initiatives and plans for the fund as we are once again reminded why we do it. Olivia’s neurosurgeon pops back up to check on her one last time as he is concerned about some potential leaking in her back. Her night nurse comes on and checks her out completely to make sure nothing is being missed.

As I lie here watching my beautiful but fragile little girl recover from surgery on her brain and spine, I am facing an amazing mom with a new baby. It is her first baby and first step in her medical journey. I hope and pray she has an exceptional village like mine to help her raise her medical child. It makes all the difference.

Some people “do” the hospital well. I am not one of them. It’s ironic, since I work here, I know. The first 48 hours in the hospital are really hard for me. I don’t sit around well, ever. I like to be busy and have a dozen frying pans in the fire at the best of times. It is always the way I have been, and short of some miracle, it is probably always the way I will be. I really love everything that I do that makes me busy: my family life, my job and the fund. My family life goes without saying. But worrying about fundraising or program planning for the Neurosurgery Kids Fund is also super rewarding. I get to have discussions with various people who all genuinely believe that kids who have had brain or spinal cord surgery or injury deserve better, people who are willing to work hard enough to find enough money to be able to make a tangible difference in these kids’ lives, and in my daughter’s life, regardless of the cost. I love it all. And I love the work part of my life as well. I love the patient population, the team I work with and the families. When I am working I am not thought of as a mother, or a wife or even a friend. I am “judged” based on my clinical skills, not how good my kids’ manners are.

Taking care of other peoples sick children is unbelievably rewarding, and truthfully much easier than taking care of my own sick child. Watching my daughter suffer is agonizing. It’s interesting when people suggest to me that I take more time off to be home with her, like time is the same thing as going to Disneyland or Hawaii. Taking time off when Olivia is really sick or in the hospital is a no-brainer for me. But time off when she is sick, but not too sick, is almost too much time for me to analyze Olivia’s situation and second guess the decisions I’ve made. It is more time to stare at her, actually trying to will her to be healthier. And while I do love the time I spend with her in the hospital, I miss the comfort of my family’s home routine. I miss reading with Kenzie and Jake and baths and watching Despicable Me in bed. Watching the other two leave at the end of the day is so hard every time. Kenzie cries and holds on to me until Brett pries her off my arm. I miss talking to Brett about little things because when Olivia in in the hospital all of our conversations are about juggling Kenzie and Jake or inquires about her pain or how often she has vomited in the last hour. I want to talk about who is making dinner or who is picking up the kids, but I already know the answer to both questions and neither of them is me.

Today was a good day. Today was a day of hope and inspiration, both from my daughter and the village that is raising her. Today was a day of visits from family, friends and even patients. It was also the day all of the cards sent for her arrived. It was an inspiring day, a day that gives me strength for a hundred more medical days.

Day three in the hospital. I got some sleep this morning, which made me feel like a new person. Olivia had a quiet day today. Her neck was pretty sore so she mostly just watched TV and slept. The day flew by with amazing visits from friends and family.

The underlying cause of Olivia’s frustration and mine is watching life go by and not being able to join in. While this hospital stay has only been four days, it has been years of sitting on the sidelines. You learn to live this parallel life, even within your own family. Sometimes you just don’t want to do it anymore.

The underlying cause of Olivia’s frustration and mine is watching life go by and not being able to join in.

This is made glaringly obvious today with Jake having his first downhill ski race, which I desperately would love to see. We had a sporting identity crisis for our kids largely influenced by Olivia’s illness. Both of the girls started out ski racing and Jake was in hockey. Like every family with kids in sports we were pulled a million different ways, but somehow figured out how, with many stops at Tim Horton’s and McDonalds on the weekend, to balance it all. Then Olivia got sick again and has essentially been sick for the past three years. This throws a whole new set of circumstances in to the mix. With her not being able to stand up for long, we need to be in three places at once, and even that is manageable if she is not in surgery or the PICU or the inpatient unit at the Stollery. Except it breaks her heart to watch us all go while she is left at home. My mom can come sit with her, but then once again she is left out. Misery loves company and if I stay, I can see she feels like we are “suffering in silence” together and it takes most of the sting out of the disappointment.

I see many medical families struggle with the same thing. If your child has trouble walking, one parent goes to the birthday party while the other one stays home because the birthday party venue is not conducive to walking. If your child is restricted in what they can eat, then one parent is constantly “on,” trying to make sure the child doesn’t eat anything that could be medically harmful. If you have to be at a million medical appointments, you get tired of dragging the whole clan with you and start to make other arrangements for the siblings so you can survive the day. Whatever the reason, the outcome is all the same: your family ends up divided. You constantly balance what is right for your medical child and what is right for your other children. If you’re not careful, you soon realize that you haven’t had a Saturday or Sunday in the same vicinity for months on end. It’s not difficult to see why the divorce rate for families with a chronically ill child is staggering.

Olivia and I have always had this tradition of late-night movies and popcorn when she is in hospital. I crawled in bed with her and after some fidgeting and fussing around so we were both comfortable, she started the movie. I asked her what she had picked and she said the movie was called Koala Kid. She explained that the movie is about a koala that is white among a pack of grey koala bears and he doesn’t fit in so he joins a carnival. For as long as I can remember my kids have had this sort of odd tradition of picking a character to be in every movie that they watch. It’s not that they do anything with the character they have picked, like acting out the role or saying their lines, it’s just who they identify with. At times this has caused some serious meltdowns and occasionally almost leads to blows, as there is a cardinal rule that two people can’t be the same character.

We thought if we told here she was normal often enough she actually would be.

As the movie began Olivia asked me who I was going to be. I threw the question back at her asked her who she wanted to be, letting her pick first, and she said, “Well obviously I am the white koala.” I said to her, “Don’t you want to be the girl koala?” knowing that this is usually the fight between her and Kenzie at home. Without hesitating she said, “No, she’s normal. I’m the white koala.” Normal. Average. Just like everyone else. These are words and statements that have taken on a negative connotation in today’s day and age where many strive to be bigger, faster and better. Striving to be “normal” can seem to some like a simple goal, or even a silly one, but for Olivia, feeling normal can at times feel impossible. When she is particularly frustrated with her medical situation, just wanting to be normal is her go-to phrase. And oddly enough, it is a phrase that I struggle with. Sometimes I say, “You are normal,” but that’s not entirely true. While there are parts of her life that are certainly normal, there is clearly a part of her life that is not normal.

When Olivia was little, Brett and I worked very hard to make sure that she felt normal. We would minimize her medical needs to her, our family, her teachers and even ourselves. We thought if we told her she was normal often enough she actually would be. The problem with this approach was that we forgot to honour what she had actually been through. I remember once she said to me, “But I’m just not normal.”

For the first time I changed my canned response and said, “Yeah, you’re right. You don’t have a life like everyone else. You have too many doctors appointments and have had too many surgeries. But look at the cool things you have got to do from having gone through all of this. You get to go to camp, you have friends you would not have had otherwise and you got to have your Make a Wish trip.”

“But I didn’t ask for any of that,” she said.

I told her, “You are right Liv, you certainly didn’t ask for any of those cool things, but you didn’t ask for any of the surgeries either. Your life isn’t the same as most of the kids in your class, and it probably never will be.” I remember her hugging me, almost relieved, like what she had always known in her head, that she didn’t have a normal life, I finally said out loud.

It’s been a long couple days. Olivia had some sort of virus on Tuesday and as a result was either crying, throwing up or sleeping. Between the ondansetron, gravol, maxeran, Zantac and morphine she found some relief at the end of the day and managed to get some much-needed sleep over night. That led us to the big day yesterday – the day of sitting up. When she woke up in the morning you could almost cut the excitement in the room with a knife. Sitting up – a task so simple, but so huge. Sitting up means the ability to use a reclining wheelchair, which means escape from her room. For me it means one step closer to home. We raised the head of her bed to 20 degrees, which doesn’t sound like much but is actually more upright than you would think.

The first half an hour goes by and she is doing great. Her back looks good, and she doesn’t have a headache. At the one-hour mark I take a peek at her back. Immediately I feel my stomach sink. Swelling. Not dramatic, but swelling none the less. It is so subtle that at first I am not sure if I might even be imagining it. I look a couple more times and then finally ask her nurse to look. She’s not concerned. Half hour later I look again. More swelling, still not dramatic but I am more convinced it is actually there. I have her neurosurgeon paged. He wanders in a bit later and takes a look. Yep, it’s leaking. Not through the skin, which is infinitely worse, but she’s leaking fluid around the valve. He says to put her back flat and leaves. I feel the tears well up in my eyes. Having a leak under the skin isn’t really surprising. She has had them before. Sometimes they have gotten better on their own and at other times they have led to months in the hospital. I knew it was a possibility but it still hurts.

Hope is a tricky thing, because you need it every day to get out of bed.

Just once I would like to sail though a procedure, heal with no complications. Why does it feel like a punch in the gut every time? The answer is because of hope. Hope is a tricky thing, because you need it every day to get out of bed, to smile at everyone and to survive chronic illness. But hope causes disappointment and pain as well. Hope makes you feel like something has failed even when it is an expected complication. Hope never totally allows you to prepare for what is to come. But hope is why Olivia is who she is. Hope has allowed us to try something new and to want a better life for her.

I have to admit I have sat here for a long time with a heavy heart and tears in my eyes as I search for the words to write an update in “Olivia’s Journey.” Olivia has been on strict bed rest for the last few weeks and has been vomiting continually. Despite this, she finds the strength to smile. The doctors placed her on intravenous nutrition to help her maintain her intake and hydration. She is such a small little bug to start with – she can’t afford to lose anything else. Tomorrow, she will need to return to the OR because something is wrong with her shunt. This will be operation 31. And to make matters worse, I have the stomach flu.

Sweet Olivia is in the operating room….

Thank god we have the medical team we do.

My dad loves to give advice. When I was younger, it used to drive me around the bend, but as I got older I realized that among the slightly long-winded explanations, there is always some deep wisdom. One of the things he stressed to me early in my career was this: surround yourself with a great team and then get out of their way. Support them. Believe in them. Never step on them and they will take you farther than you will ever get on your own. I have always taken this to heart.

Advocating for your child is a skill and an art at the same time. Assembling a medical team that wants to work for you and your child is critical.

Early on in my life, certainly in my career, I got the greatest sense of satisfaction from praise. Being told I was a good nurse, a good mother, a good wife meant more to me than most other things in my life. But as I have grown confident in myself, I find a far greater sense of satisfaction in watching others grow and soar than any accolades I ever receive. I couldn’t care less if I get credit for the Neurosurgery Kids Fund or Camp Everest or even my family, as long as they all end up amazing. So over the years I have worked and fought for a great neurosurgical team to work with, great nurses in my clinics and on the ward and a great team to help me raise my family. For my children I need a strong family, strong marriage, great friends and in Olivia’s case, a great medical team. It took me a while to figure out what that meant for her, for my husband and for myself. Over the years it took some tweaking of her team to find the “right” people to help us care for her – a team that fit our vision of what we wanted her life to be, what we thought was realistic and what we thought she deserved. After working so hard to find that team, it would seem crazy to me to then not have faith in them and get out of their way.

Finally after years of struggling and failing to control her medical situation, I handed it over to her team. I remember sitting down with her team and saying, “I can’t make these decisions any more. I just need to be her mom,” and feeling this tremendous weight lifted from my very soul. I could physically feel it.

Advocating for your child is a skill and an art at the same time. Assembling a medical team that wants to work for you and your child is critical. I have learned this skill from watching countless parents do it poorly and others who are absolutely amazing at it. At times I think people equate advocating for your child with controlling the entire medical situation. This isn’t the best way to ensure your child’s care, or the best way to save your sanity. Not trying to control the situation is not the same as being uninterested or uninformed. I always have an opinion about what she needs. The difference is that instead of trying to learn more than the people who have spent their lives learning neurosurgical procedures, I have become an expert in her.

I know Olivia inside and out. I know when she is good, when she is off, and when she is really sick. I know her medical history, although at times even that can be a huge amount of information to sift through. I know to bring her in for a checkup or follow-up when she is feeling great, because even though going to another appointment is the last thing I want, her medical team needs to see who she is when she is great so they can remember what we are all trying to achieve. I know when to stand my ground and when to listen because I may not be able to see the entire situation objectively. On Monday when her neurosurgeon told me she needed to go back to the operating room, I knew she wasn’t well when she was standing upright, but I left him to chart the course of actions. The decision was easy. I have learned that relying on the team doesn’t mean you are weak or uninformed or uncaring. As parents we sometimes put a tremendous amount of time and energy in to researching our child’s conditions and possible solutions. Education and information is power. It is equally important to make sure you assemble the right team for you and your child, a team that fits your beliefs, your thoughts and your needs. Taking the time and energy to do this will not only help save a bit of your sanity, but it also means even when you are burnt out or exhausted, your child will receive the very best care from that team, since they are as invested as you are in her health and happiness.

The valve in Olivia’s spine is fixed. It’s back to bed rest for at least a week to try to get the incisions to heal. I had a night of nausea and general grumpiness. I’m not sure if she is getting the flu I had. I sure hope not. Operation number 31 is under our belt. Lucky number 31? I hope so. Thanks so much to everyone for your thoughts and prayers over the past few weeks. It constantly amazes me how good people really are.

I had a panic attack last night. All of a sudden at 10 p.m., the light at the end of this particular hospital admission seemed to go out for me. How is her back possibly going to heal? If it does heal, what if it doesn’t work? In the midst of my panic I sent out two SOS texts to very good friends hoping one of them happened to have their phone on. Instantly my phone binged twice. Both were awake. Both wanted to know what was going on. As I spoke to one of them and texted the other I realized how much art there is to being the friend of a chronically ill child. One of my friends went over the medical details with me, both of us trying to determine if there is a medical reason for my panic and the other one texted me to breathe and try to relax. Both recognized it was late and I was tired, but both took different approaches to get to the same point: we are here for you and you will get through this one way or the other.

You can Google what to say to the parent of a chronically ill child. You will instantly get thousands of hits of blogs or lists or articles on what we all want you to say to us when we are in a crisis situation. There are an equal number of lists of what not to say to us when we are losing our minds. Sometimes when I read them I think, “Who the heck would ever want to be the friend of a chronically or acutely ill child? There are so many rules about what to say and how to say it, things that if you don’t do them exactly right we will surely implode and never recover.”

The truth is, most, if not all parents of a chronically ill child are unbelievably strong, they just might not know it yet. That’s where friends and family come in. Lists of what you should or should not say are good. Not great but good. They are generic and generally a common-sense list of statements that help if you have never been around a sick child, or sick person for that matter, in your entire life. I hesitated to write a note on this topic for fear that all of my friends and family are going to worry that I mean them. In truth I am very lucky. My friends and family have been “doing sick” with me since Olivia was born and have come to do it really well. The thoughts in this blog are just that, thoughts. They are not rules, or lists or anything of that sort for people to live or die by. They are simply things friends and families have done in my life that have left an impression on me. If you are reading this and are a friend of mine, you’re totally not the example of what not to do. That is that other friend I have. You know the one…

For me, being the friend of someone with a sick child starts with a conscious decision you have to make. Are you in or are you out? Are you totally in? Neither answer is wrong. Where I think harm can be done is when you sign up for one category and then when the going gets tough, decide to switch to another team. So think about where you fit in, what you can commit to, and what role you can play early on and then try to stick to it. Obviously life happens and things will change that may not be in your control. If your role has to change, that’s OK too, just be honest about it. I’m not saying that if you email your friend that you need to take a break from the friendship that they are going to bake you a loaf of bread and send you a “Thank you for being honest card.” The truth is they will probably be hurt and angry and even say a few unpleasant things about you in their head or even out loud. But they won’t continue to rely on you, they will be able to seek out a new place to find that support. Of course, it’s much easier to say than do. It’s even more rarely ever done, but it’s something to consider none the less.

The truth is, most, if not all parents of a chronically ill child are unbelievably strong, they just might not know it yet. That’s where friends and family come in.

Not many friends opt out, but it does happen. “Out” means you don’t have the time, energy or resources to be a source of support for the parent or caregiver. It does not mean you are a bad person, should be burned at the stake or are going to you-know-where when your time expires. I have had many friendships come and go in my life. When Olivia was born, Brett and I had some friends that had a lot going on in their lives, things that were out of their control or for whatever reason, prevented them from maintaining a friendship with us in any meaningful way. There were some hurt feelings. As the years move on, some of these relationships have repaired themselves and have become the friendships on which we rely the most.

I think the lack of disappointment and fact that trust between us was never violated or broken allowed this.

On the other hand, we have had some real struggles with some people. Relationships that were once strong suddenly ended over seemingly silly events. Making a conscious decision to not be there for a friend or family member when their child is sick should not be done lightly as it is very difficult, if not impossible to recover from. It’s like not going to someone’s wedding, or major event like the birth of their child. You can never get that moment back, the memory of that event will always be with you absent. Even if your relationship is struggling when the hospitalization occurs, think long and hard about how you handle it. This may be one of those times in your life where you do in fact “suck it up” and be there for them because if you choose not to, it is almost the same as letting the relationship go entirely.

Being “in” is where most people fall. This is where you drop in and email, text or give a phone call on a regular basis to see how things are going. You are the fantastic people in our lives who bring meals, fruit and sneak in the occasional bottle of wine in the bottom of a care package. You know to always call before you come, just in case things have changed medically or we are just too tired to have visitors. You judge the length of your visit from the cues both Olivia and I give, which can be different from visit to visit. You get that when the nurse comes in to help her to the bathroom, you don’t offer to step out, you just do it, and that when she starts to puke you give me a quick hug, ask if I need any help and then cut your visit short, even though you drove for 35 minutes to get there.

All of your seemingly small offers, collectively, leave a huge impression on my soul and my family. Thanks.

And then there are the “totally in” friends and family. You are my 10 p.m. calls. You are the ones that never miss an operation or a hospitalization even if your visit doesn’t come until late at night. You know to pace yourself in our friendship, because while everyone will come for the initial hospitalization or even the day of the surgery, you will be there in a month or two or 18 when many others have gone back to their normal routine. You don’t promise stuff you can’t deliver. You have read about my child’s illness and while you may not understand it all, you have taken the time to learn the basics. You don’t offer advice on what to do, but you know sometimes I need to run through things out loud to get it straight in my head. If you do have advice or a question you phrase it in a seamless way that doesn’t make me feel like I have missed something or am being crazy. You come to the hospital, late at night, even when I tell you not to because you know I need you. You are there at 3 a.m. when we arrive and are still there in the afternoon when there is a chance there may be a catastrophic outcome. You show up at 6 a.m. and leave a coffee with a note at my bedside, because you know I need sleep more than a visit. You offer to update everyone else because I am too tired to.

I can call you and impose, totally screwing up your plans, and I never even know that I did because you just make it work. You don’t go skiing when you really want to, so you can hang out with us and we don’t feel left behind yet again. You can make me laugh when all I want to do is cry and crack an inappropriate joke about my child’s illness because you know I will think it is funny. You will periodically cry with me and for me at the same time because you know I am dying a bit inside. You will drive up for a day on the weekend when it’s the last thing you feel like doing. You won’t go to Phoenix because you know I can’t do it without you. You will call me and offer a holiday for me and my other kids because you understand they are struggling too. You will spend hours on the phone talking with me when I feel like all of this is my fault. You are in for the long haul and even though we both may stumble, we will always find our way back to the friendship we both signed up for. You are why I can get up, every morning, and do this all again. You allow me to breathe.

Olivia is still flat in bed, but out of her room. I have figured out how to steer the huge bed, and I have only ran over two people’s toes and one old man. I’ve made bracelets, coloured pictures, watched a thousand episodes of Austin & Ally and I think am actually starting to enjoy them, much to my dismay. I had dinner with my mom and the kids at the hospital last night in the garden and enjoyed, to the tips of my toes, watching my girls lay in bed together and chat about what they are going to do when we get home. I’m taking some excellent advice and trying to live for the moment instead of worrying about what is to come on Monday. I hope everyone enjoys the early spring today before the polar vortex descends again tomorrow.

HERE’S HOW YOU HELPED

- You made a point to visit us in the hospital once a week.

- You cut your visit short when you saw it wasn’t a great day, even though you drove 35 minutes to get here.

- You dropped a meal off for us when we got home.

- You went late to a party when you saw I needed to chat.

- You discretely stepped out of the room for a few minutes when bathroom time came.

- You never say you know what I am going through.

- You took my other kids out to an event.

- You took my shopping list(and money and bought my groceries.)

- You stayed away when you had a cold but still called me.

- You keep in touch with calls, texts, Facebook and words of encouragement.

Friendships in the hospital, and really among all sick kids, are fast and deep. I’m not entirely sure if it is the common bond of being a sick child or the fact they spend such a concentrated amount of time together that leads to this, but some of Olivia’s closest friends have come from the hospital. Sometimes I wonder if the fact that some of these friends may die makes them shed their shyness and dive in heart first. Sometimes I worry as well.

At the age of 10, Olivia has been to the funerals of four friends and has missed the funeral of two others that she would have desperately liked to have gone to, but was too sick. She has stuffies in her room that have a special place as they have been given to her by two amazing moms after they lost their daughters. They are the only two stuffies that have their own beds and that regularly get dusted. Jake touched one of them one time, and it is the only time I have actually seen Olivia punch him. I didn’t even really punish her because I could see the panic and anguish. Facing the mortality of children is crushing, beyond crushing, each and every time.

Last December was the closest we have ever come to losing Olivia. There were moments when I thought we had lost the battle. Now I think all the time, “What would I be doing if we had lost her?” Sometimes I hear a song on the radio and think, “I should remember this song just in case I ever have to plan her funeral,” and then just as quickly I feel like I am going to throw up for even letting the thought cross my mind. I am a nurse –

it’s a funny profession as we are always talking about boundaries. You have to have boundaries. You can never cross these boundaries for fear of being thought of as weak or unprofessional. How anyone could honestly think that we are going to take care of and at times lose children and not be absolutely devastated is beyond me. There are times that we have lost a patient and I have cried every day, for weeks, on the way home from work. But I could never say that out loud for fear of being thought of as having bad boundaries. When I talk to the surgeons we often wonder what people think we are like. Do they really think we come to work, operate on children, see the devastating effects of brain tumours or bleeds or car accidents and then just walk out like it was just another day at the office? All of us can remember every patient we have lost, the circumstances around that death and the impact of that day on the family. And I have learned to love the kids, grieve for their loss, use what I have learned from them to better who I am both personally and professionally and then tuck them away in my heart so I can get up the next day and care for the next critically ill child. I never forget them.

The walls in my office are papered with pictures, notes and funeral notices of the children that I have lost in my practice. It is overflowing, but I can’t take even one down as even the thought of rearranging them brings me anxiety and sadness. It is these children that give me the sense of urgency for change. Waiting to build an environment that is conducive to support and research and sometimes just pure, uncensored fun cannot wait, because if it has to, some of these children will no longer be here.

Olivia and her new little friend sold their cupcakes at a makeshift cupcake stand outside of the pediatric surgical unit. They wore matching night gowns and giggled every time someone bought a cupcake for two dollars.

In the three years we have been doing Camp Everest we have lost 15 per cent of our campers. Unacceptable. And while I am realistic and realize that for now we can’t save every child, as a community we can maximize every year, every day, every single minute that they have. This is what makes me put my sick child to bed on day 23 in the hospital and then at 11:30 p.m. head to my office to pay invoices, work on fundraisers and plan the summer camps for next year, because they all just deserve more and it is up to all of us to give them that.

I tried to get Olivia up again on Monday and her back leaked under the skin again. I was absolutely devastated, but as always, I have to suck it up and cope with it as there is nothing but time that can help. Being able to get up in the wheelchair is a huge help. Olivia and her new little friend sold their cupcakes at a makeshift cupcake stand outside of the pediatric surgical unit. They wore matching night gowns and giggled every time someone bought a cupcake for two dollars. They sold all the cupcakes in 30 minutes, but made a friendship that will last a lifetime. I will try to get her up again next Monday. It’s hard to believe we are coming up on a month here. Hopefully we’ll be home next week. My fingers are crossed.

YOU CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE!

Donate today to help make a child’s life exponentially better through the great work we are doing at the NKF.